KEY WEST, Fla. — The crew of Coast Guard Cutter Mohawk returned to their homeport in Key West, Saturday, after a 60-day patrol in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of America, where crew members boarded and escorted two sanctioned oil tankers.

Operating in support of Operation Southern Spear, Mohawk’s crew partnered with Department of War and Department of Homeland Security assets as well as additional Coast Guard units to board and escort the two sanctioned vessels, preventing the illicit trade of crude oil in violation of international sanctions.

“Our dedicated crews are the frontline of maritime security,” said Cmdr. Taylor Kellogg, commanding officer of Mohawk. “Their vigilance and expertise were instrumental in the successful interdiction and escort of these tankers, preventing illicit oil from destabilizing the Western Hemisphere. This is a clear demonstration of the Coast Guard’s commitment to enforcing international law and our vital role in the Joint Force. I’m proud of their selfless service and devotion to duty.”

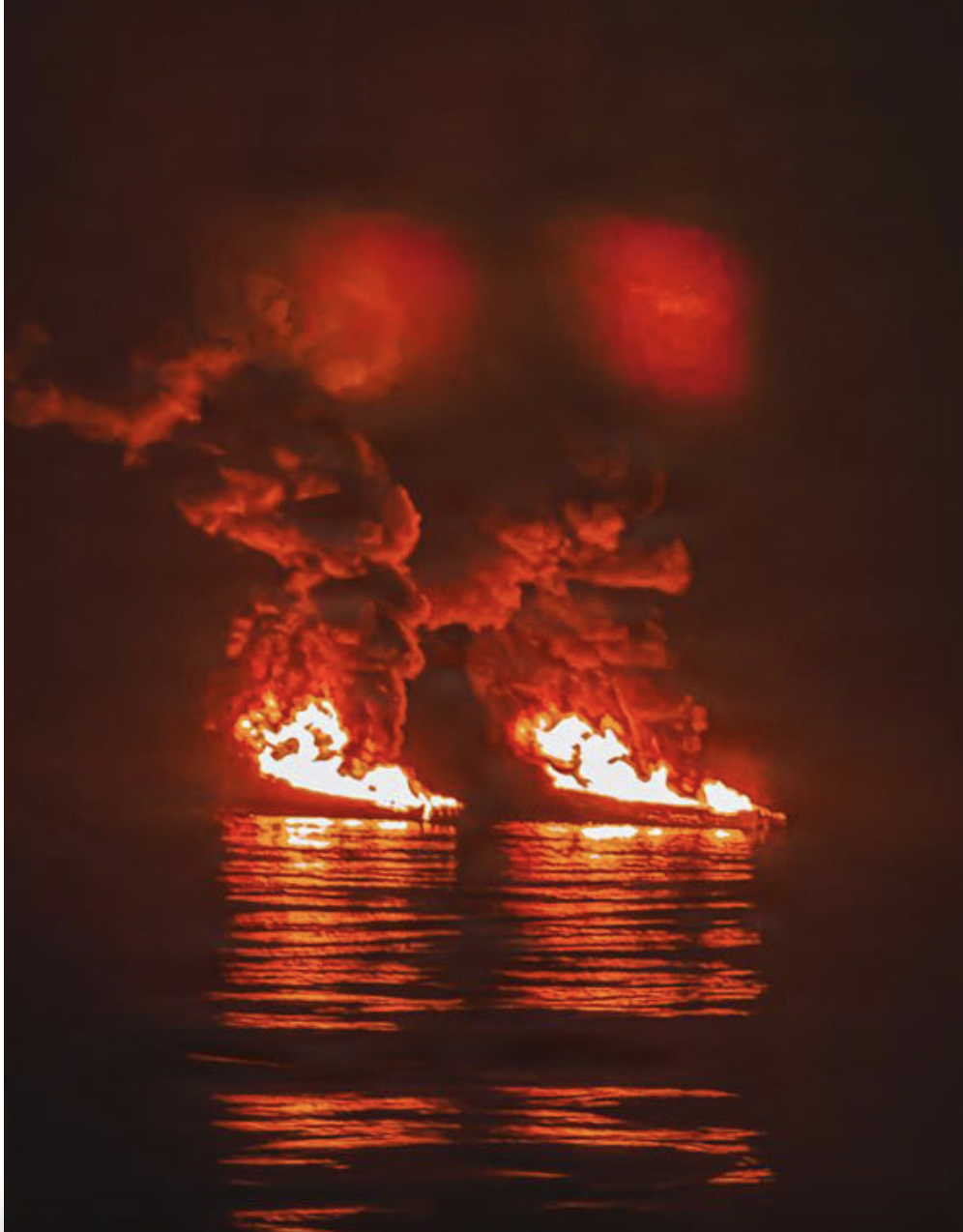

On Dec. 20, a Coast Guard tactical law enforcement team with DoW support intercepted and boarded the Panamanian-flagged motor tanker Centuries. Subsequently, Mohawk escorted Centuries during its transit from the Caribbean Sea to the Gulf of America, where the tanker moored for further disposition in coordination with the Centuries’ flag state.

On Jan. 15, a Coast Guard tactical team with DoW support intercepted and seized the Venezuelan-linked, Aframax motor tanker Veronica, prompting Mohawk’s crew to quickly transit back to the Caribbean Sea and provide escort duties. Following a boarding by a joint warfare team, Mohawk escorted Veronica to a secure anchorage in the Caribbean Sea.

The back-to-back escorts totaled 17 days and covered a combined distance of 2,700 nautical miles.

Unique statutory authorities enable the Coast Guard to enforce international and domestic law in the maritime domain, deploying assets to conduct missions in U.S. waters and on the high seas. The Coast Guard’s involvement in these maritime activities was conducted under Title 14, U.S. Code and in accordance with customary international law. The Coast Guard exercises these authorities to protect maritime safety, security and U.S. interests.

For media inquiries, contact lantpao@uscg.mil.

###

About the U.S. Coast Guard and Operation Southern Spear

The U.S. Coast Guard’s missions are enabled by a unique blend of military, law enforcement and humanitarian capabilities. The Coast Guard is the principal federal agency responsible for maritime safety, security and environmental stewardship in U.S. ports, waterways and on the high seas.

Operation Southern Spear is a multi-agency effort led by the DoW to counter illicit maritime trade and enforce international sanctions. By leveraging joint capabilities, the operation aims to disrupt transnational criminal organizations and maintain stability in the maritime domain.

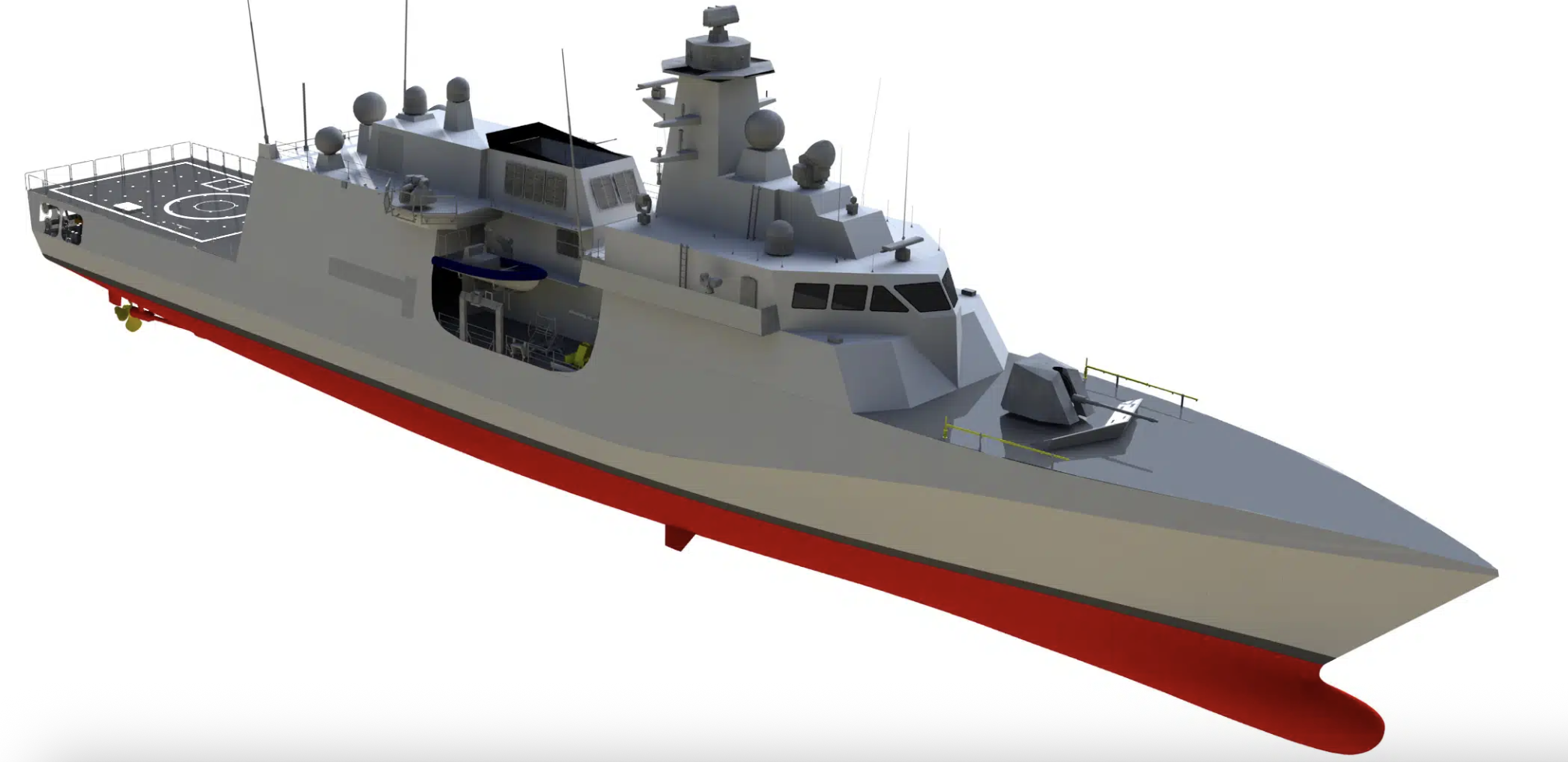

Mohawk is a 270-foot, Famous-class medium endurance cutter homeported in Key West. An asset of U.S. Coast Guard Atlantic Area, the cutter’s primary missions include counter-narcotics, alien interdiction, homeland security, and search and rescue in support of U.S. interests in the Western Hemisphere.

Based in Portsmouth, Virginia, U.S. Coast Guard Atlantic Area is responsible for all Coast Guard missions east of the Rocky Mountains to the Arabian Gulf, spanning five districts and 40 states. It oversees a wide range of operations, including counter-drug and alien interdiction, enforcement of federal fishery laws, and search and rescue operations in support of Coast Guard missions throughout the Western Hemisphere. In addition to surge operations, Atlantic Area is a force provider of surface and air assets to the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific to combat transnational organized crime and illicit maritime activity.

For more information on how to join the U.S. Coast Guard, visit GoCoastGuard.com to learn about active duty, reserve, officer and enlisted opportunities. Information on how to apply to the U.S. Coast Guard Academy can be found here.