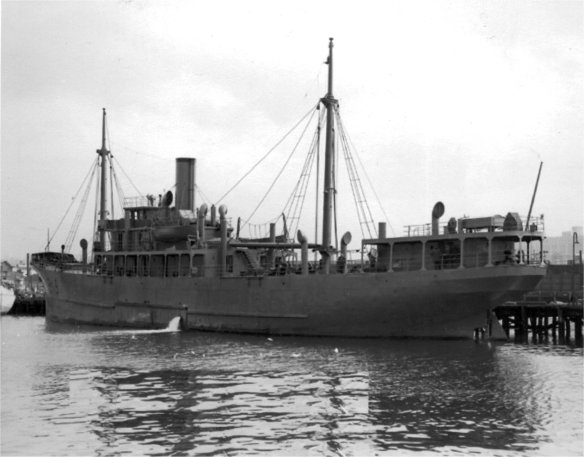

Coast Guard Cutter 16, an 83-foot wooden patrol boat assigned to Coast Guard Rescue Flotilla One, sits out of the water in Poole, England, in 1944. On D-Day, the crew of CGC-16 saved the lives of 126 Allied troops, more lives than any other vessel present that day. (U.S. Coast Guard photo)

| Feature Release |

U.S. Coast Guard 8th District Public Affairs Detachment Texas |

Coast Guard veteran turns 100, reflects on ‘scary days’ and ‘unbelievable sights’ of D-Day invasion

|

Official headshot of Michael J. Swierc, who enlisted in the Coast Guard on Aug. 11, 1942, and trained as a motor machinist’s mate before deploying overseas for the first wave of the D-Day invasion. Swierc, who turned 100 years old on Nov. 6, 2021, received the Bronze Star Medal for helping save 126 Allied troops from drowning in the English Channel on June 6, 1944. (U.S. Coast Guard photo, courtesy Pam Manka) |

Story by Petty Officer 1st Class Corinne Zilnicki

Nearly 80 years have passed since Mike Swierc vaulted over the side of a ship hundreds of yards off Utah Beach during the first wave of the D-Day invasion. But for Swierc, a 100-year-old Coast Guard veteran, the memories of those fateful days and nights have not faded from his mind.

“The night of the invasion was unbelievable,” said Swierc. “There was a continuous flash of lightning in the sky and we could hear the bombs. It was nonstop fire.”

Facing off against 28 German heavy artillery batteries and multiple 88 mm machine guns was not exactly what Swierc had expected upon enlisting in the Coast Guard. He and his younger brother had preemptively joined the service in 1942 hoping to protect domestic waterways and scour eastern U.S. coastlines for enemy submarines.

Instead, the farmer’s son found himself weaving through the frigid waters of the English Channel more than 5,000 miles from his hometown of Falls City, Texas.

A natural and seasoned mechanic, Swierc had spent the first 22 months of his Coast Guard service swept up in a whirlwind of basic training and diesel engine schools before deploying overseas for the Normandy invasion.

The 31-day journey from Bayonne, New Jersey, to Ireland was fraught with difficulty. Swierc passed the days aboard his transport ship peeling potatoes, scrubbing dishes and wincing at the sound of the wind lashing against the bulkhead.

“Somehow, I never got seasick,” Swierc marveled. “But we faced the most terrible storm when we crossed the Atlantic.”

The 500 destroyers, escort ships, battleships and aircraft carriers in Swierc’s convoy kept their bows pointed doggedly into the fierce wind and arrived overseas on schedule. Upon reaching Ireland, the Coast Guardsmen joined U.S. Navy sailors in joint training sessions, honing their skills in small-boat handling, ship-to-shore movement, beach landings and general maintenance. As D-Day loomed closer, Coast Guard, Navy, and British Royal Navy personnel prepared their ships for the channel crossing.

Swierc’s cutter, an 83-foot, wooden patrol boat called Coast Guard Cutter 16, was assigned to Rescue Flotilla One, a collection of 60 ships that had been hastily summoned only a few weeks prior. Although the wooden cutters of “the matchbox fleet” were initially designed to hunt submarines, their crews were now charged primarily with rescuing Allied soldiers during the invasion.

“The name of the game was search and rescue,” Swierc said. “I think we did our fair share.”

At around 4 a.m. on June 6, 1944, the Allied assault force departed from the rendezvous point and headed for the coast of France. Heavy seas battered the boats and soaked the men, many of whom were desperately seasick. Bullets and shellfire roared to life overhead and pummeled the water all around the convoy as it approached Utah Beach.

“We didn’t really have time to be scared,” explained Swierc. “We got in there and got after it.”

As soon as CGC-16 arrived off the beachhead, Swierc and his crew dove into action and began plucking survivors from the water around the USS PC-1261, the first ship sunk on D-Day. The submarine chaser had led the first wave of landing craft toward Utah Beach and was obliterated when an artillery shell slammed into its starboard side, instantly killing nearly half the crew.

With shellfire peppering the water around them and the explosions of nearby mines rattling the deck beneath their feet, the Coast Guard crew calmly began extracting shipwreck survivors from the oil-slicked waves.

Upon spotting two injured Allied soldiers in the water, Mike Swierc leaped off the cutter, swam 40 yards through enemy gunfire and fastened a rescue line around the men.

“The one guy said, ‘Don’t worry about me, just get my buddy,’” recalled Swierc. “But I looked at his buddy, and he was bleeding with his head in the water. He had already passed away.”

Unflinchingly, the CGC-16’s head mechanic swam back through the 54-degree water as crew members aboard the cutter reeled in the two soldiers. This was only one of many daring plunges Swierc took into the water that day.

“We were out there swimming our hearts out,” said Swierc. “That water was icy cold but you just didn’t pay attention to it, you just swam.”

With 90 rescued troops safely aboard, the CGC-16 crew sped away from the PC-1261 wreckage site and delivered the survivors to the USS Joseph T. Dickman, a nearby transport ship-turned-hospital platform.

Immediately after handing over the last survivor, the CGC-16’s skipper, Coast Guard Lt. j. g. R. V. McPhail, maneuvered the cutter back into the line of fire to recover more wounded soldiers and sailors from another damaged landing craft. The vessel had struck a mine and was listing on its side, threatening to trap more than 30 stranded crew members underwater. Swierc and his shipmates tossed lines to the men and hoisted them aboard only seconds before the landing craft completely capsized, narrowly avoiding crushing CGC-16 in its rapid descent.

Undeterred, the CGC-16 crew rushed to rescue survivors from a third landing craft decimated by artillery shells less than a mile offshore, nosing past mines and through unceasing shellfire to reach the men.

“The whole deck was completely covered with survivors, most of them traumatically injured,” Swierc said. “It was a sad situation, but we were sent there to do it, and we did it the best we knew how.”

Despite having little formal medical training, Swierc found himself administering first aid to those sprawled across the decks of his ship. Hands that had spent countless hours picking cotton and repairing tractors now steadily injected morphine into the veins of wounded Allied soldiers and marked each man’s forehead with an “X” to record the dosage. After dulling the survivors’ pain, Swierc and his shipmates secured them in baskets and passed them to personnel aboard the Dickman.

All told, the crew of CGC-16 rescued 126 men on June 6, more than any other ship present that day. Along with his shipmates, Swierc earned both the Navy and Marine Corps and Bronze Star Medals for his gallantry and lifesaving actions.

Although his award citation lauds his “cool courage” and “devotion to duty,” Swierc said he was merely doing what he was supposed to do.

The achievements of Swierc and the CGC-16 crew aligned with the overall efforts of Coast Guard Rescue Flotilla One, which saved more than 400 men on D-Day alone and rescued 1,438 Allied troops before the end of June.

Even when the D-Day invasion ended and Allied forces gained a firm foothold in France, Swierc’s commitment and loyalty did not waiver. Along with most of his fellow CGC-16 crewmen, he eagerly volunteered to deploy to the Pacific theatre.

However, the war ended before he got the chance to make the journey.

In September of 1945, the head mechanic of the CGC-16 boarded a transport ship and headed back across the Atlantic with a souvenir tucked in his bag: a set of wrenches from his cutter, which along with 58 other ships of the matchbox fleet had been sunk, burned or cut up for scrap.

Although he was proud to have served his country, Swierc was eager to return to Falls City and reunite with his family. As though flipping back to a page in a familiar book, Swierc resumed helping his father on the farm, picking cotton and shucking corn with the same hands that had pulled wounded, waterlogged soldiers out of the English Channel.

Shortly after returning home from the war, Swierc began working at his brother’s grocery store, where he soon met and inadvertently annoyed his future wife. Despite a rocky start, the two eventually went on their first date at a local cafe, got married in 1948 and had eight children. Swierc, who turned 100 years old on Nov. 6, 2021, and is now surrounded by 44 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren, described his life since D-Day as “rich in love.”

“It’s my family’s love that keeps me going,” he explained with a chuckle and a smile. “This is just the first hundred years of my life. Now I’m going to start on my second hundred.”

Allied troops storm Utah Beach under heavy German artillery and machine gun fire in Normandy, France, June 6, 1944. More than 23,000 men of the U.S. 4th Infantry Division landed on Utah Beach, the westernmost of the assault beaches. (U.S. Coast Guard photo) |

|

Members from Coast Guard Sector/Air Station Corpus Christi attend a birthday celebration for Michael J. Swierc, a Coast Guard veteran who turned 100 years old, Nov. 6, 2021, in Falls City, Texas. Swierc was presented with a hand written letter from the Commandant, as well as a Coast Guard ensign signed by members of Sector/Air Station Corpus Christi and a unit ball cover. (U.S. Coast Guard photo, courtesy Sector/Air Station Corpus Christi) |

A socket wrench set originally kept on board Coast Guard Cutter 16, an 83-foot wooden patrol boat whose crew saved the lives of 126 Allied troops on June 6, 1944. Michael J. Swierc, 100-year-old Coast Guard veteran and head mechanic aboard the cutter, kept the set of tools as a souvenir from his service during WWII. (U.S. Coast Guard photo, courtesy Pam Manka) |

|