Naval News reports the launching of the first of four PPX project Offshore Patrol Vessels for the Italian Navy. The contract for the first three ships was signed in mid 2023 and the first keel was laid 12 December 2024.

As I noted at the time,

Fincantieri is the parent company of the Marinette based shipyard that has been building Freedom class LCS and will be building the US Navy’s new frigates. That shipyard also built USCGC Mackinaw, the 16 Juniper class WLBs, and the 14 Keeper class WLMs.

We know now that Fincantieri has finished with the Freedom class LCSs and will build only two Constellation class frigates.

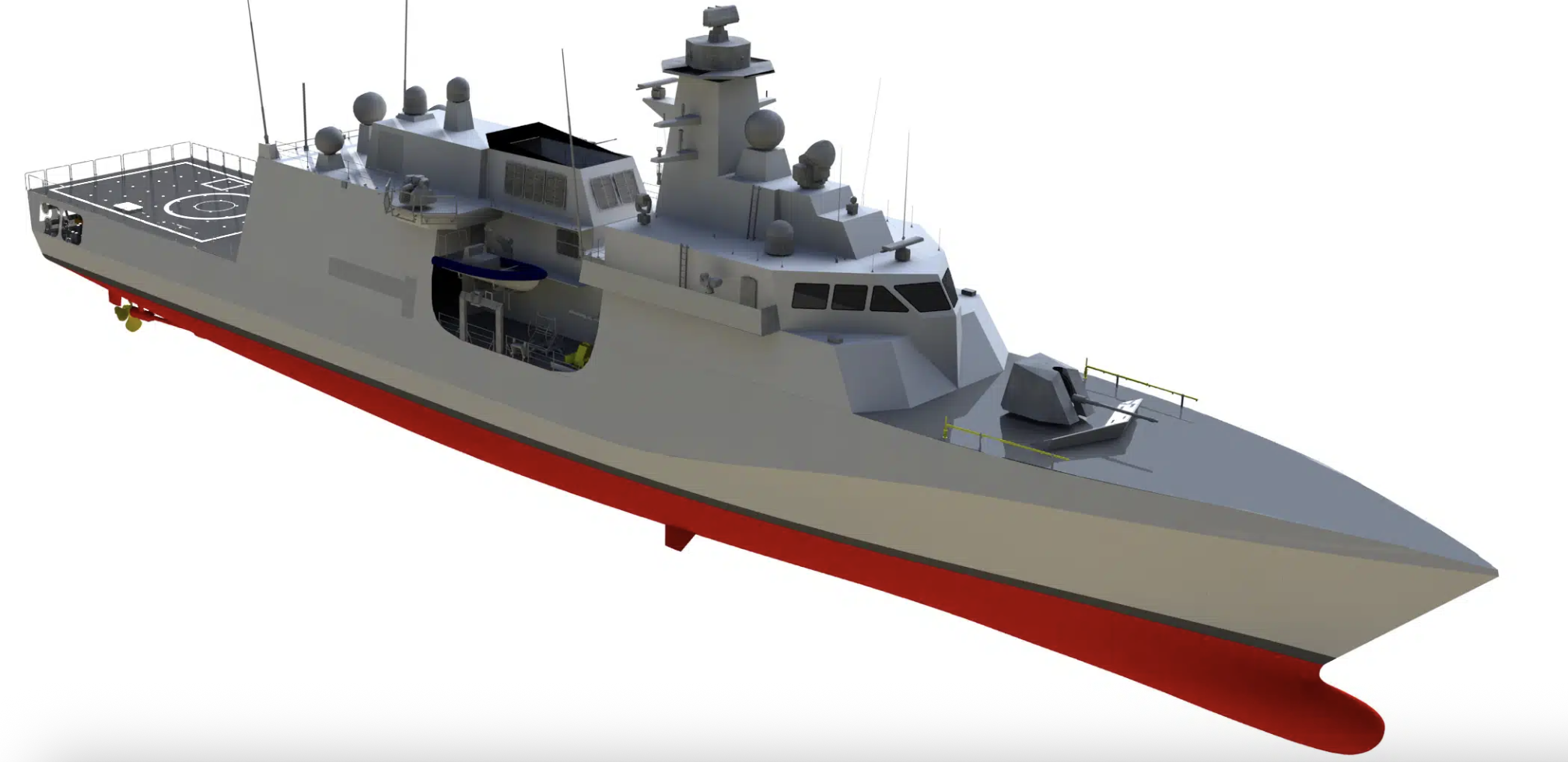

The new generation will be able to operate both rotary-wing manned and unmanned platforms. (Fincantieri)

We need more new ships, and we need them fast. Looks like with few modifications, we could build these as complements to currently contracted OPCs to give us a true WMEC replacement. They are built as combatants to Naval specifications. They can operate H-60 sized helicopters and UAS. They are designed for pollution response. They have the potential for adding a towed array and possibly AAW missiles. Unlike most cutters these ships have redundant propulsion systems in two separate engine rooms. These could serve as corvettes in wartime.

An earlier Naval News report included more technical information,

“With a full load displacement of about 2,400 t, an overall length of about 95 meters (311.6 feet–Chuck), a maximum beam of 14.2 meters, a construction height of 8.4 meters and a maximum draft of only 5.4 meters to operate from a wide range of harbours. The OPV hull design is characterized by bow area featuring a bulb and a completely covered mooring area, alongside active stabilizer fins amidships to ensure operational capability in high sea state conditions and rough weather.

“The CODLAD (COmbined Diesel-eLectric And Diesel) propulsion system is configured on two shaft lines, each including an 8 MW (ISO 3046) MTU 16V8000M91L diesel engine and a 500 kW Marelli reversible electric motor, directly connected to a double input/single output gearbox and controllable pitch propellers, while the rudders are of the conventional type. The diesel engines together with the electric ones must ensure a maximum speed exceeding 24 knots, while the electric motors provide… operating speeds up to 10 knots. Maximum range is 3,500 nm at a speed of 14 knots (more at lower speeds, particularly if the electric propulsion is used–Chuck), with a maximum mission endurance of 20 days.

“The electric power generation and distribution plant is based on four Isotta Fraschini V1708C2ME5 diesel gensets of around 680 kWe each divided in two separate electrical stations. The compartment arrangement for the propulsion and power generating equipment guarantees 50% of the propulsion power with damage to a single compartment and 50% of the electrical power with damage to two contiguous compartments.”