The report below is from the CG-9 website.

MH-65 upgrades were invaluable to mission success in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian

The Air Station Miami crew evacuates a person in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian. In addition to Air Station Miami’s MH-65Es and HC-144Bs, the coordinated rescue included one MH-65E from Air Station Houston and two MH-65Ds from Air Station Savannah. Total statistics for the coordinated rescue: 46 lives saved, 36 lives assisted and 19 pets saved. U.S. Coast Guard photo by Air Station Miami.

Hurricane Ian caused nearly 150 fatalities when it swept through Florida in late September 2022 and has been cited as the deadliest hurricane to hit Florida since 1935. In the search and rescue efforts that followed, Air Station Miami crewmembers played a pivotal role in rescuing both human and animal survivors. According to the pilots, upgrades on the Coast Guard’s MH-65E proved vital during multiple rescue missions. In the days following the storm they were faced with harried conditions when fuel stops were limited, communications were intermittent and lives depended on the speed and awareness of the crew.

The upgraded MH-65E, or Echo, sports an all-glass cockpit and Common Avionics Architecture System (CAAS) that replaced legacy analog components. The new system aligns with Federal Aviation Administration next-generation requirements that call for performance and space-based navigation and surveillance, allowing for more three-dimensional approaches and flight patterns as well as higher visibility of the helicopter by other on-scene aircraft.

Integral to the CAAS is the automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast, or ADS-B, which allowed command aircraft (both Coast Guard HC-144 and Navy P-3) to track the MH-65E even when it was no longer visible to the crews. The moving map on the pilot screens can be overlayed with the traffic collision avoidance system (TCAS), which helps deconflict airspace with multiple aircraft maneuvering in tight quarters. The display can be placed across four multi-function display (MFD) screens and is accessible to both pilots.

“The TCAS was immensely helpful, especially being able to use the moving map overlay,” said Lt. Audra Forteza. “There were so many aircraft in the area, both military and civilian, and not everyone was making traffic calls as they should be – the TCAS allowed us to quickly and efficiently find the most imminent threat and maneuver to maintain separation. Knowing where exactly to look for a target made identification much faster and allowed us to focus on the mission at hand vice continually searching for other aircraft.”

The crewmembers were equally impressed by the bingo fuel alerts, an aviator term used to describe the minimum fuel an aircraft requires to land safely at its designated landing site. Fuel stops were severely limited because of widespread power outages on the ground. This meant that finding an airport with a generator strong enough to facilitate refueling was largely based on recommendations from other parties in communication with the aircrews. “Word of mouth was key to success for aircrews operating the area to determine which airports had fuel,” Forteza said. “And the people at the airfields were extremely accommodating in getting crews food, fuel, water and bathrooms.”

The MFD screens were also very useful when it came to hoisting survivors out of difficult situations while maintaining situational awareness and control of the aircraft. Forteza was able to monitor her co-pilot safely and effectively while they operated the hoist in a series of challenging urban environment rescues over the course of several days.

Additionally, utilizing the upgraded radar weather mode allowed for safe navigation between hurricane bands as the crews searched for survivors by painting a clearer, more accurate picture of the evolving weather situation even when their in-flight tablets did not have reception. In response to Hurricane Ian, Air Station Miami pilots flew a total of 46 hours over several days. Forteza and Lt. Danielle Benedetto personally contributed to saving the lives of 16 people, as well as five cats and three dogs. The air station fully transitioned to the MH-65E in July 2021.

Air Station Miami crew, from left: Petty Officer 2nd Class Tyler Kilbane, Petty Officer 2nd Class Nick Rodriguez, Lt. Audra Forteza and Lt. Danielle Benedetto. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

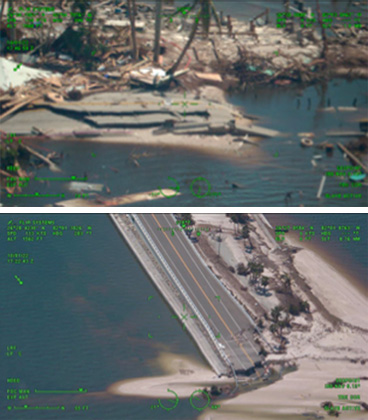

Live shots of Hurricane Ian damage taken by Minotaur-equipped HC-144 aircraft were used to support the Incident Management Team. U.S. Coast Guard photos.

MH-65E transition

The Coast Guard has completed 52 out of 98 total conversions including avionics upgrades to the Echo configuration and Service Life Extension work. Air stations that have completed the transition and number of aircraft:

| Houston | 3 |

| Miami | 5 |

| Port Angeles, WA | 3 |

| Barbers Point, HI | 4 |

| North Bend, OR | 5 |

| Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron | 12 |

| Humboldt Bay, CA | 3 |

| San Francisco | 7 |

Next up for conversion are Atlantic City, N.J., and Savannah, GA

For more information: MH-65 Short Range Recovery Helicopter Program page and Minotaur Mission System Program page