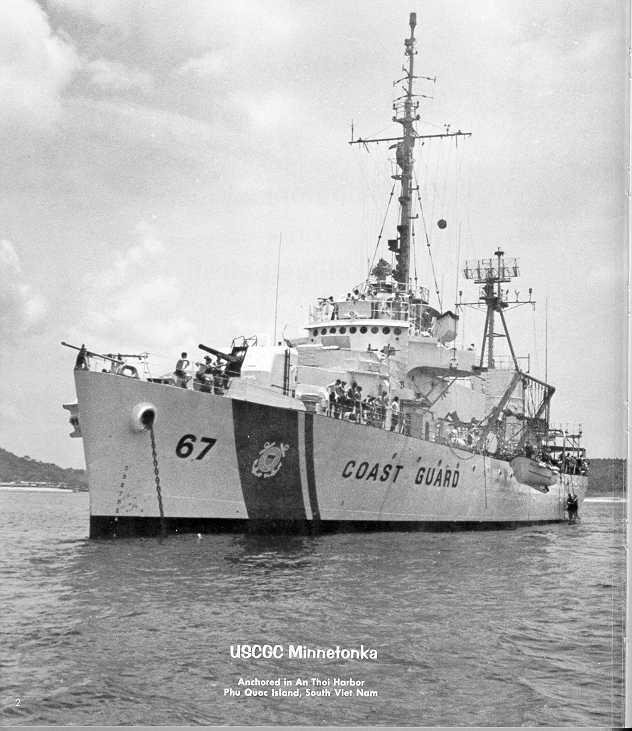

Coast Guard Cutter John Witherspoon, the service’s 58th fast response cutter, in Key West, Florida, where the Coast Guard accepted delivery on Nov. 7, 2024. The cutter will be homeported in Kodiak, Alaska, after it is commissioned. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Below is a report from the Acquisitions Directorate (CG-9).

The news release indicates there is only one additional Homeport (Seward, AK) currently planned.

I think the statement that there will be three of the class in Kodiak is new. Previously I had heard two. There are three in Ketchikan. The Wikipedia page indicates that while Frederick Mann (WPC-1160) will go to Kodiak initially, ultimately it will go to Seward, so three in Kodiak may be temporary.

One of the 67 cutters, USCGC Benjamin Dailey (WPC-1123) had a serious fire while in a shipyard and has been scrapped, so there is one fewer than you might assume. That explains why this is #58 but only 57 “are in service.”

I did a post in May speculating on where additional members of the class will be homeported. Since then, we learned that the three additional FRCs I expected to go to D14, will be going to Guam. If my projections are correct, the Coast Guard will be contracting for at least two more FRCs, five if the Coast Guard establishes a base for three in America Samoa. The revised program of record calls for 71 FRCs which would, given the loss of one, mean the Coast Guard will have procured 72, five more than currently contracted, so I think the projections are pretty close.

Bollinger typically delivers four FRCs a year, so we can probably look forward to seeing the final FRC, WPC-1172, commissioned in 2028.

Nov. 8, 2024 —

The Coast Guard accepted de358 livery of the 58th fast response cutter (FRC), Coast Guard Cutter John Witherspoon, on Nov. 7 in Key West, Florida. John Witherspoon is the first of three FRCs to be homeported in Kodiak, Alaska.

The cutter’s namesake, John Gordon Witherspoon, became the first African American to command a medium endurance cutter. When he assumed command of Coast Guard Vessel Traffic Services-Houston/Galveston, he became the first African American to command afloat and ashore units. A well-respected, compassionate and admired leader, he served as a popular mentor to an army of “teaspoons,” an affectionate term for those who sought sage counsel from Witherspoon about advancing their Coast Guard careers.

Witherspoon enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1963 and rose to the rank of quartermaster first class within eight years. Witherspoon eventually set his sights on becoming a commissioned officer and successfully received a waiver for the two-year college education requirement for Officer Candidate School. He was commissioned as an ensign in June 1971.

During his service, Witherspoon received the Coast Guard Meritorious Service Medal, two Coast Guard Commendation Medals and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Roy Wilkins Renown Service Award.

Witherspoon passed away in 1994 at the age of 54. In honor of his service and guidance to many, the Coast Guard established the Captain John G. Witherspoon Inspirational Leadership Award after his passing, which is given to officers who demonstrate his qualities of “honor, respect and devotion to duty.” The following year, the National Naval Officers Association created the Captain John G. Witherspoon for Excellence in Leadership and Mentoring Award. And in 2003, Witherspoon was inducted into the Caldwell County School’s Hall of Fame in North Carolina.

The Sentinel-class FRCs are replacing the 1980s Island-class 110-foot patrol boats, and possess 21st century command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance equipment, with improved habitability and seakeeping. A total of 67 FRCs have been ordered to date to perform a multitude of missions that include drug and immigrant interdictions, joint international operations and national defense of ports, waterways and coastal areas. Each FRC is named after an enlisted Coast Guard hero who performed extraordinary service in the line of duty.

Fifty-seven of the 67 FRCs that have been ordered are in service: 13 in Florida; seven in Puerto Rico; six each in Bahrain and Massachusetts; four in California; three each in Alaska, Guam, Hawaii, Texas and New Jersey; and two each in Mississippi, North Carolina and Oregon. In addition to Kodiak, future FRC homeports include Seward, Alaska.

For more information: Fast Response Cutter Program page