Polar Star at Mare Island Dry Dock LLC undergoing the fourth phase of its five-year Service Life Extension Project. U.S. Coast Guard photo by Cmdr. Jeremy Courtade.

Below are two news releases, first one from Coast Guard News, the second from the Acquisitions Directorate (CG-9).

The Coast Guard has been working very hard to make sure that Polar Star can meet her annual commitment to open a path for resupply of the Antarctic Base at McMurdo, but it has to have been hard on the crew. They just completed the fourth phase of a five-part Service Life Extension Program (SLEP), but unlike the single phase SLEPs and MMAs we are seeing with the buoy tenders and medium endurance cutters at the Coast Guard Yard, here the crew stays aboard. After 138 days on the resupply mission, instead of returning to Seattle, their homeport, they went to Vallejo, California, where they spent about 140 days. Altogether, 285 days away from homeport, and over a one-year period, more days in Vallejo than in homeport.

Polar Star has only one more of these to go, but it looks like the Crew of USCGC Healy is going to go through the same 5-year SLEP cycle, where they will spend more time in Vallejo than in their homeport. This is just wrong. There are only two yards on the West Coast that can accommodate ships of this size. The Navy, with its huge presence, is a strong competitor for the use of the one in Seattle. By contrast the Bay Area has virtually no Navy presence. It is likely the Icebreakers will have to use the yard in Vallejo for almost all their drydocking. Maybe it is time to change their homeport to somewhere in the San Francisco Bay Area, maybe even Vallejo.

Improvements are planned for Base Seattle, largely on the assumption that the Polar Security Cutters (PSC) will be based there, but they can expect to run into the same problem. Given the greater size of the PSCs and the long-term probability the Navy presence in Seattle will remain large and may well increase, the problem is not going away. The dry dock in Vallejo was built to accommodate battleships. It is big enough.

U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star (WAGB 10) (left) sits moored next to U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy (WAGB 20) at Coast Guard Base Seattle, Aug. 25, 2024. The Polar Star and Healy are routinely deployed to Arctic and Antarctic locations to support science research or help resupply remote stations. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Lt. Chris Butters)

Coast Guard heavy icebreaker returns to Seattle following Antarctic deployment, months-long Service Life Extension Project in California

SEATTLE — The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star (WAGB 10) and crew returned to Seattle, Sunday, after 285 days away from the cutter’s home port.

Following a 138-day deployment to Antarctica supporting Operation Deep Freeze 2024, the Polar Star reported directly to Mare Island Dry Dock (MIDD) LLC. in Vallejo, California, to commence the fourth phase of a five-year Service Life Extension Project (SLEP).

The work completed at MIDD is part of the in-service vessel sustainment program with the goal of recapitalizing targeted systems, including propulsion, communication, and machinery control systems, as well as effecting significant maintenance to extend the cutter’s service life.

Polar Star’s SLEP work is completed in phases to coordinate operational commitments such as the cutter’s annual Antarctic deployment. Phase four began on April 1, 2024, targeting three systems:

- Boiler support systems were recapitalized, including the electrical control station that operates them.

- The heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system was refurbished through the overhaul of ventilation trunks, fans and heaters that supply the cutter’s berthing areas.

- The flooding alarm system was redesigned, providing the ability to monitor machinery spaces for flooding from bow to stern.

Additional work not typically completed every dry dock included removing and installing the starboard propulsion shaft, servicing and inspecting both anchor windlasses, inspecting and repairing anchor chains and ground tackle, cleaning and inspecting all main propulsion motors and generators, installation of an isolation valve to prevent seawater intrusion into the sanitary system, and overhauling the fuel oil purifier.

Phase four of Polar Star’s SLEP took place over approximately 140 days and represented a total investment of $16.8 million. By replacing outdated and maintenance-intensive equipment, the Coast Guard will mitigate lost mission days caused by system failures and unplanned repairs. The contracted SLEP work items and recurring maintenance is taking place within a five-year, annually phased production schedule running from 2021 through 2025.

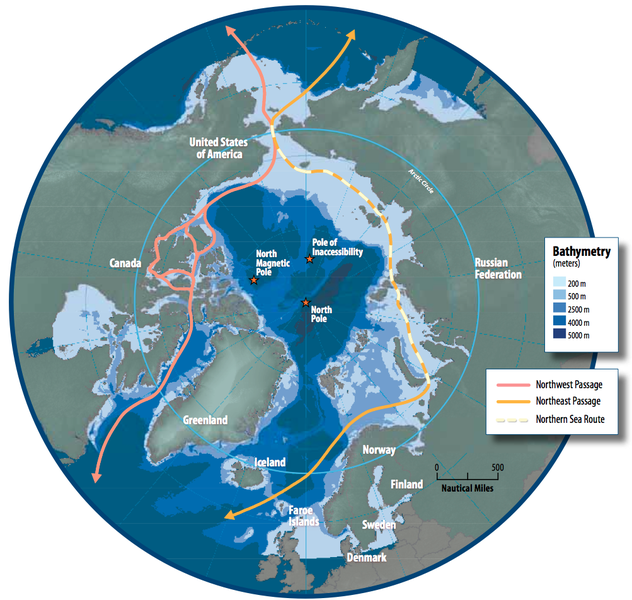

The Coast Guard is investing in a new fleet of polar security cutters (PSC) that will sustain the service’s capabilities to meet mission needs in both the Arctic and Antarctic regions. The SLEP allows Polar Star to continue providing access to the Polar regions until the PSCs are operational and assume the high latitude missions. Polar security cutters will enable the U.S. to maintain defense readiness in the Polar regions; enforce treaties and other laws needed to safeguard both industry and the environment; provide ports, waterways and coastal security; and provide logistical support – including vessel escort – to facilitate the movement of goods and personnel necessary to support scientific research, commerce, national security activities and maritime safety.

“Completing a dry dock availability is a positive milestone, and despite challenges due to being away from home port, our crew’s energy and resilience inspires me every day,” said Capt. Jeff Rasnake, Polar Star’s commanding officer. “The amount of time and effort put into Polar Star and its mission is truly remarkable. The dedication and teamwork displayed across all stakeholders exemplifies the Coast Guard’s flexibility and commitment to ensuring the continued success of Operation Deep Freeze as well as strengthened partnerships among nations invested in the Antarctic latitudes. I look forward to observing how this crew will continue to grow as a team and to discovering what we can accomplish together.”

Along with the rigorous maintenance schedule, Polar Star held a change of command ceremony on July 8, 2024, in Vallejo, where Rasnake relieved Capt. Keith Ropella as the cutter’s commanding officer. Rasnake served as the deputy director for financial management procurement services modernization and previously served as Polar Star’s executive officer. Ropella transferred to the office of cutter forces where he will oversee the management of the operational requirements for the cutter fleet and develop solutions for emerging challenges facing the afloat community.

Polar Star is the Coast Guard’s only active heavy polar icebreaker and is the United States’ only asset capable of providing year-round access to both polar regions.

Commissioned in 1976, the cutter is 399 feet, weighing 13,500 tons with a 34-foot draft. Despite reaching nearly 50 years of age, Polar Star remains the world’s most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker with the ability to produce up to 75,000 horsepower. Polar Star’s SLEP is important to the survival of the Antarctic mission and crucial to the well-being and success of Polar Star and crew during these long missions.

Coast Guard completes fourth phase of service life extension work on Polar Star

Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star completed the fourth phase of its five-year Service Life Extension Project (SLEP) at the Mare Island Dry Dock LLC in Vallejo, California. The cutter departed the San Francisco Bay Area on August 22, for its homeport in Seattle.

The SLEP, a key initiative within the Coast Guard’s In-Service Vessel Sustainment (ISVS) Program, aims to extend the service life of the Polar Star by modernizing targeted systems, including propulsion, communication, and machinery control systems. Concurrent with the SLEP work, crews conducted significant maintenance efforts to ensure the cutter remains capable of operating within some of the most extreme environmental conditions on earth.

SLEP work on the Polar Star is conducted in phases to align with the cutter’s operational commitments, such as the cutter’s annual Antarctic deployment. Phase four began on April 1, 2024, focusing on the following systems:

- Heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems were refurbished with ventilation trunks, fans and heaters to improve air circulation and maintain comfortable living environment for the ship’s crew during extended deployments.

- Boiler support systems were recapitalized, including the electrical control station that operates them to generate reliable heating and steam supply to the water maker.

- The flooding alarm system was redesigned to enable the crew’s ability to monitor the ship’s machinery spaces for flooding from bow to stern.

Additional work completed during this phase, beyond routine dry dock maintenance, was critical to ensuring the Polar Star’s operational readiness. This included significant overhauls and inspections of key propulsion and anchoring systems that are essential for the cutter’s operational performance.

Kenneth King, Program Manager for the ISVS Program, commented on the milestone, saying, “I am tremendously proud of the joint In-Service Vessel Sustainment Program, the Long Range Enforcer Product Line team and their significant efforts in completing Phase 4. Our dedicated professionals continue to exemplify our service’s core values to ensure Polar Star meets its multifaced missions in the polar regions until the arrival of the Polar Security Cutter Fleet.”

For more information: In-Service Vessel Sustainment Program page and Polar Security Cutter Program page.