Below is a news release from Canadian shipbuilder, Seaspan.

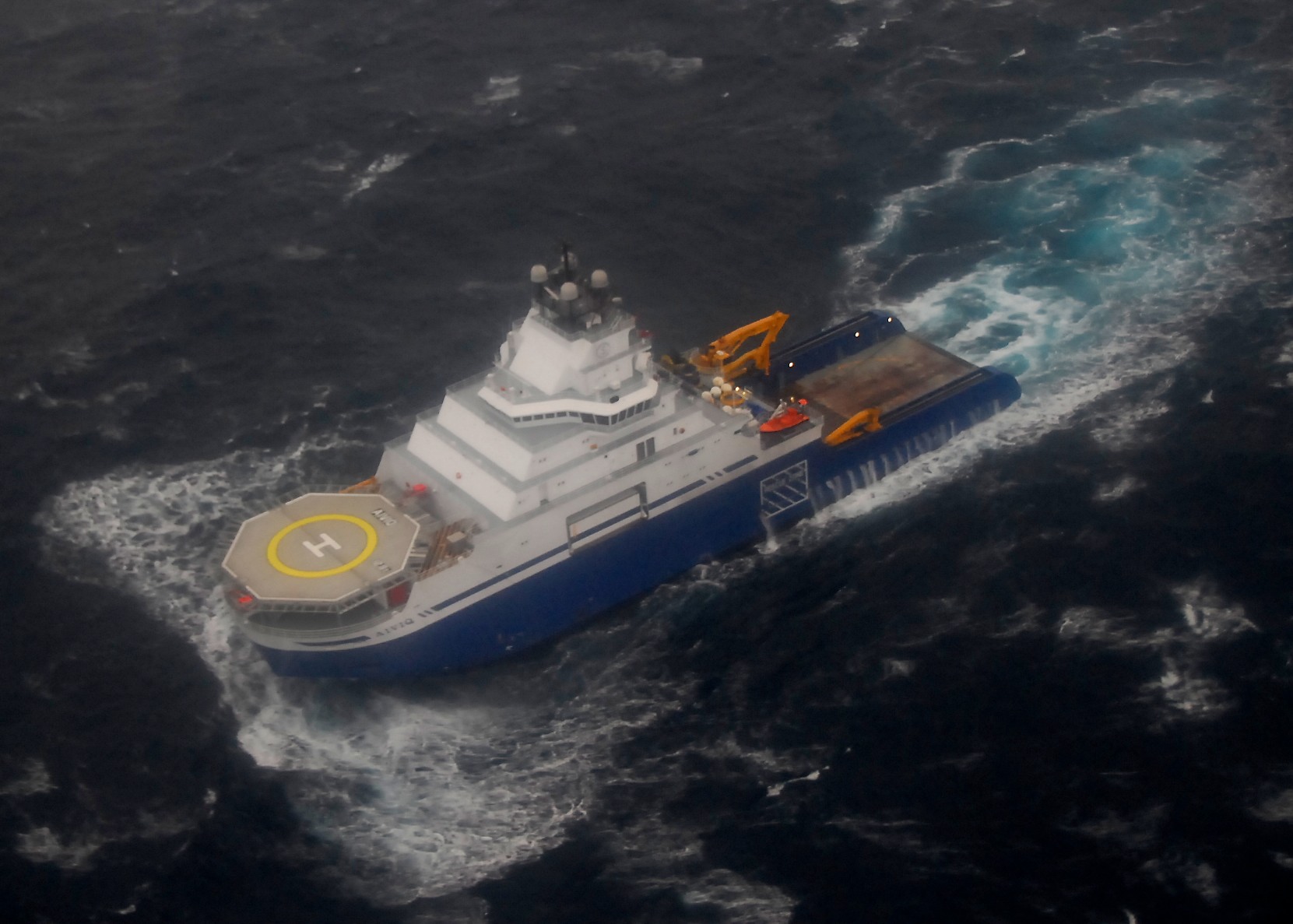

March 7, 2025 – North Vancouver, BC – Today, Seaspan Shipyards (Seaspan) has been awarded the construction contract to build one of the Canadian Coast Guard’s (CCG) new heavy polar icebreakers.

The polar icebreaker will be built entirely in Canada at Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards, located in North Vancouver, British Columbia. With the contract now in place, Seaspan is ready to cut steel on this ship and begin full-rate construction on Canada’s newest vessel under the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS). Construction of this ship will support the work of a team of more than 1,000 local shipbuilders and a broad Canadian supply chain of over 800 Canadian companies contributing massive strategic value, innovation and economic benefits to Canada.

Building this complex and densely-outfitted multi-mission ship will mark the first time a polar icebreaker has been built in Canada in more than 60 years and will have more advanced capabilities than the CCG’s current heavy icebreakers. Once delivered, this made-in-Canada heavy polar icebreaker will be one of the most advanced and capable icebreakers in the entire world. It will be one of only a handful of Polar Class 2 ships in operation and will allow for the CCG to operate self-sufficiently year-round in the high-Arctic, down to temperatures at -50°C.

The new polar icebreaker will be the seventh vessel designed and built by Seaspan under the NSS. It will also be the fifth Polar Class vessel to be built for the CCG, and one of up to 21 icebreaking vessels overall that Seaspan is constructing.

Functional design of the polar icebreaker was completed in 2024 by Seaspan, prior to the start of construction. For this ship, Seaspan worked extensively to build out the largest marine design and engineering team in Canada, which includes Seaspan employees and Canadian partners, while simultaneously working alongside established Finnish companies who have extensive experience in designing Arctic-going vessels.

Seaspan is the only Canadian shipyard with the expertise, facilities, and domestic supply-chain to build polar icebreakers in Canada. Official start of construction for this new heavy polar icebreaker is scheduled for April 2025.

QUOTES

“Today’s contract signing is the next step in our journey of fulfilling the vision of the National Shipbuilding Strategy, which is to build ships for Canada, in Canada, by Canadians. The NSS is demonstrating that a made-in-Canada approach is not only possible, but also imperative to our security and sovereignty. We look forward to starting construction on this ship next month, and to building more Polar Class vessels for Canada and our Ice Pact partners.”

- John McCarthy, CEO, Seaspan Shipyards

“The contract awarded to Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards for the build of a new polar icebreaker is a significant step forward for Canada’s economic and natural resource sectors. This advanced vessel will not only ensure safe and efficient navigation in our polar regions but also support the sustainable development of our natural resources. By enhancing our icebreaking capabilities, we are opening new opportunities for economic growth, scientific research and environmental stewardship. This project exemplifies our commitment to leveraging cutting-edge technology to benefit our economy and protect our unique polar environments for future generations.”

- The Hon. Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Energy and Natural Resources and MP for North Vancouver

“Today marks a significant milestone in our commitment to enhancing our nation’s maritime capabilities. The contract awarded to Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards for the build of a new polar icebreaker underscores our dedication to ensuring safe and efficient navigation in Arctic regions. This state-of-the-art vessel will not only strengthen our icebreaking fleet, but will also support critical scientific research and environmental protection efforts, and ensure national security in the Arctic. We are proud to take this step forward in strengthening our maritime infrastructure for safeguarding Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic.”

- The Hon. Jean-Yves Duclos, Minister of Public Services and Procurement and Quebec Lieutenant

“The National Shipbuilding Strategy is providing the Canadian Coast Guard with its fleet of the future. The polar icebreaker to be built by Vancouver Shipyards will be able to operate in the Arctic year-round, further bolstering our ability to deliver crucial services to Northern communities and support Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic.”

- The Honourable Diane Lebouthillier, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard

“Our partnership with Seaspan to construct a polar icebreaker underscores our government’s steadfast commitment to ensuring the Canadian Coast Guard can continue to protect Canada’s sovereignty and interests, while also revitalizing Canada’s shipbuilding industry, creating high-paying jobs and maximizing economic benefits across the country.”

- The Honourable François-Philippe Champagne, Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry

QUICK FACTS

- The polar icebreaker will be 158 metres long and 28 metres wide, with a design displacement of 26,036t.

- Highlights of key design features, include:

- IACS Polar Class 2 (PC2) Heavy Icebreaker

- More than 40MW of installed power

- Ice-classed azimuthing propulsion system

- Complex, multi-role mission capability

- Scientific Laboratories

- Moon Pool (to allow for safe deployment of equipment from within the ship)

- Helicopter flight deck and Hangar

- Vehicle Garage and future Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS) capability

- Seaspan has already gained significant experience designing and building Polar Class vessels including three offshore fisheries science vessels which are now in service with the CCG; an offshore oceanographic science vessel that will be delivered to the CCG in the coming months; and a class of up sixteen multi-purpose icebreaking vessels (also Polar Class) that is currently in Construction Engineering.

- Seaspan is one of the most modern shipyards in North America, following its privately funded $200M+ shipyard modernization, development of a skilled workforce and state-of-the-art, purpose-built infrastructure to deliver large, complex vessels.

- Under the NSS, Seaspan has become a major economic and job creation engine. According to an economic analysis conducted by Deloitte, Seaspan has contributed $5.7 billion to Canada’s GDP between 2012-2023, while also creating or sustaining more than 7,000 jobs annually.

- Seaspan’s NSS supply-chain has now grown to ~800 Canadian companies from coast-to-coast, with more than half being SMEs.