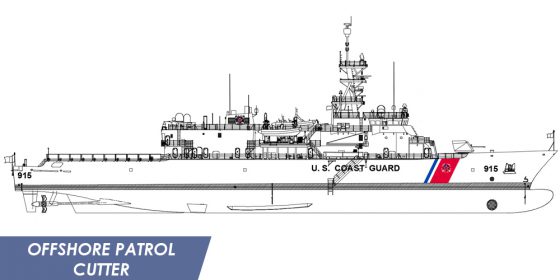

Offshore Patrol Cutter future USCGC ArgusThe Congressional Research Service has once again updated their look at Coast Guard Cutter procurement.

I have quoted the summary below and will comment on some of the questions.

The Coast Guard’s program of record (POR) calls for procuring 8 National Security Cutters (NSCs), 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPCs), and 58 Fast Response Cutters (FRCs) as replacements for 90 aging Coast Guard high-endurance cutters, medium-endurance cutters, and patrol craft. The Coast Guard’s proposed FY2020 budget requests a total of $657 million in procurement funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs.

NSCs are the Coast Guard’s largest and most capable general-purpose cutters; they are intended to replace the Coast Guard’s 12 aged Hamilton-class high-endurance cutters. NSCs have an estimated average procurement cost of about $670 million per ship. Although the Coast Guard’s POR calls for procuring a total of 8 NSCs to replace the 12 Hamilton-class cutters, Congress through FY2019 has funded 11 NSCs, including the 10th and 11th in FY2018. Six NSCs have been commissioned into service. The seventh was delivered to the Coast Guard on September 19, 2018, and the eighth was delivered on April 30, 2019. The ninth through 11th are under construction; the ninth is scheduled for delivery in 2021. The Coast Guard’s proposed FY2020 budget requests $60 million in procurement funding for the NSC program; this request does not include funding for a 12th NSC.

OPCs are to be smaller, less expensive, and in some respects less capable than NSCs; they are intended to replace the Coast Guard’s 29 aged medium-endurance cutters. Coast Guard officials describe the OPC program as the service’s top acquisition priority. OPCs have an estimated average procurement cost of about $421 million per ship. On September 15, 2016, the Coast Guard awarded a contract with options for building up to nine OPCs to Eastern Shipbuilding Group of Panama City, FL. The first OPC was funded in FY2018 and is to be delivered in 2021. The second OPC and long leadtime materials (LLTM) for the third were funded in FY2019. The Coast Guard’s proposed FY2020 budget requests $457 million in procurement funding for the third OPC, LLTM for the fourth and fifth, and other program costs.

FRCs are considerably smaller and less expensive than OPCs; they are intended to replace the Coast Guard’s 49 aging Island-class patrol boats. FRCs have an estimated average procurement cost of about $58 million per boat. A total of 56 have been funded through FY2019, including six in FY2019. Four of the 56 are to be used by the Coast Guard in the Persian Gulf and are not counted against the Coast Guard’s 58-ship POR for the program, which relates to domestic operations. Excluding these four, a total of 52 FRCs for domestic operations have been funded through FY2019. The 32nd FRC was commissioned into service on May 1, 2019. The Coast Guard’s proposed FY2020 budget requests $140 million in acquisition funding for the procurement of two more FRCs for domestic operations.

The NSC, OPC, and FRC programs pose several issues for Congress, including the following:

- whether to provide funding in FY2020 for the procurement of a 12th NSC;

- whether to fund the procurement in FY2020 of two FRCs, as requested by the Coast Guard, or some higher number, such as four or six;

- whether to use annual or multiyear contracting for procuring OPCs;

- the annual procurement rate for the OPC program;

- the impact of Hurricane Michael on Eastern Shipbuilding of Panama City, FL, the shipyard that is to build the first nine OPCs; and

- the planned procurement quantities for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs.

Bertholf Class National Security Cutters (NSCs):

If there is going to be a 12th NSC, it almost certainly has to be funded this year. Future years will see the Polar Security Cutters and OPCs further crowding the budget. Frankly I see little to choose between the NSC and OPC for peacetime missions, but the replacement of the legacy fleet is becoming urgent and the price of the NSCs has decreased as funding became more regular, so a 12th might be reasonable. If we had started the OPC program earlier, it might have offered a lower cost alternative to additional NSCs, but we will not be ready to start multi-ship procurements of the OPCs until FY2021 and then only at the rate of two per year if we follow current planning.

Argus Class Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPCs):

There is probably good reason to accelerate the OPC program beyond the two per year currently planned to begin in FY2021. If we maintain that rate, the last 210 foot WMEC will not be replaced until 2028, the last 270 not until 2034. I expect we may see some catastrophic failures that will result in either sidelining ships or unacceptably high repair costs, before the program of record is complete.

The Coast Guard should plan on expediting testing of the first OPC so that production could move from the current contract with options to a true Multi-Year contract as soon as the design has proven successful.

We probably will need more than 25 OPCs. The Coast Guard has operated more than 40 cutters of more than 1,000 tons for decades. It seems likely we are going to need more than 36 total NSCs and OPCs. (See the discussion about the Fleet Mix Study below.)

Webber Class Fast Response Cutters (FRCs):

We are nearing the end of the Webber class program with 52 of the 58 program of record vessels, plus four additional vessels for Patrol Forces South West Asia (PATFORSWA), already funded. Buying only two for FY2020 raises the unit costs of these vessels. Congress has consistently increased purchases to four or even six per year when only two have been requested. Adding the final two additional FRCs intended to replace the 110s assigned to PATFORSWA would bring the total buy to four. That would leave only four to be purchased in FY2021 which could wrap up the funding. The question is, will Congress stop the program at the 64 vessels total when there may be justification for more?

Impact of Hurricane Michael:

The Coast Guard budget is not the place to provide disaster relief for businesses. Maybe they have insurance. Maybe the state or Federal Government wants to provide aid, but renegotiating the contract for OPCs is not the way to do it. No way should it come out of the Coast Guard budget.

If on the other had we do renegotiate the contract, it is not to late to make it a “Block Buy.”

One solution might be for the contract to be converted to a block buy, using purchase amounts no more than current contract with options. That would assure the contractor and its creditor that they would have a steady stream of work. The contract might even have options for production of additional ships at rates higher than two per year.

We Need a New Fleet Mix Study:

The number of OPCs and FRCs actually required to fulfill Coast Guard statutory missions was examined in a fleet mix study (see pages 19 and 20 of the report) that found that the Program of Record (8 NSCs, 25 OPCs, and 58 FRCs) fell far short of the number of vessels required to meet all statutory requirements. Phase One of the study (2009) found that the total “objective” requirement was 9 NSCs, 57 OPCs, and 91 FRCs. Phase Two found that only 49 OPCs would be required but found the same requirements for NSCs and FRCs (see page 22).

The problem is that the analysis is getting pretty old and its assumptions were wrong. The Coast Guard will have at least 11 NSCs. The FRCs appear to be more capable than anticipated. Perhaps most importantly, the study assumed the NSCs and OPCs would use the “Crew Rotation Concept,” resulting in an unrealistic expectation for days away from homeport. From my point of view, the study failed to even consider the requirement to be able to forcibly stop a medium to large size ship being used as a terrorist weapon. None of our ships are capable of doing that reliably, and even our ability to stop small fast highly maneuverable ships under terrorist control is far from assured, even if the objective fleet were available.

The Procurement, Construction, and Improvements FY2020 budget request is about $1.2B. Adding NSC #12 and a pair of FRCs using the costs in the CRS report ($670M/NSC plus 2x$58M/FRC) which are probably high for the current marginal costs, would still leave the PC&I budget under the $2B/year the Coast Guard has been saying they need and about $250M less than the FY2019 PC&I budget.

For the Future:

While we are thinking about cutters, with the FRC program coming to an end, it is not too early to think about the 87 foot WPB replacement. I think there might be a window to fund them after the third Polar Security Cutter if we have our requirements figured out. That means preliminary contracts such as conceptual designs have to be done during the same period we are building PSCs, e.g. FY2022 and earlier. .

To avoid always being constantly behind the power curve, as we have been for the last two decades, we really need a 30 year shipbuilding plan. The Navy does one every year. There is no reason the Coast Guard should not be able to do one as well. The Congress has been asking for a 25 year plan for years now, but so far no product.

Thanks to Grant for bringing this to my attention.