Since our last look at this report, there have been four updates. (See the latest version here.)

We now have the Senate Appropriations Committee’s (SAC) views on this part of the FY2021 DHS Appropriations Act. The Senate committee, like its counterpart in the House, has recommended approval of the Administration request for $555M that would fund the second Polar Security Cutter.

I have reproduced the section on Senate Activity (page 25/26) below. Note there is also mention of renovation of the Polar Star and acquisition of a future Great Lakes icebreaker as well:

Senate

The Senate Appropriations Committee, in the explanatory statement for S. XXXX that the committee released on November 10, 2020, recommended the funding level shown in the SAC column of Table 2.

The explanatory statement states (emphasis added):

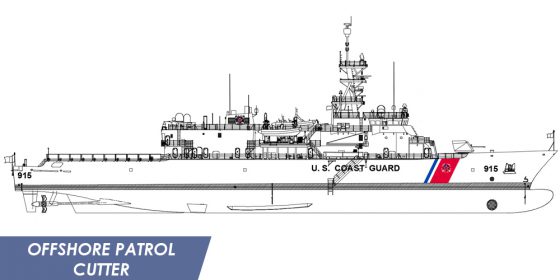

Full-Funding Policy.—The Committee again directs an exception to the administration’s current acquisition policy that requires the Coast Guard to attain the total acquisition cost for a vessel, including long lead time materials [LLTM], production costs, and postproduction costs, before a production contract can be awarded. This policy has the potential to make shipbuilding less efficient, to force delayed obligation of production funds, and to require post-production funds far in advance of when they will be used. The Department should position itself to acquire vessels in the most efficient manner within the guidelines of strict governance measures. The Committee expects the administration to adopt a similar policy for the acquisition of the Offshore Patrol Cutter [OPC] and heavy polar icebreaker.

Domestic Content.—To the maximum extent practicable, the Coast Guard is directed to

utilize components that are manufactured in the United States when contracting for new

vessels. Such components include: auxiliary equipment, such as pumps for shipboard

services; propulsion equipment, including engines, reduction gears, and propellers;

shipboard cranes; and spreaders for shipboard cranes. (Pages 71-72)

The explanatory statement also states:

Great Lakes Icebreaking Capacity.—The recommendation includes $4,000,000 for preacquisition activities for the Great Lakes Icebreaker Program for a new Great Lakes

icebreaker that is as capable as USCGC MACKINAW. The Coast Guard shall seek

opportunities to accelerate the acquisition and request legislative remedies, if necessary. Further, any requirements analysis conducted by the Coast Guard regarding overall Great Lakes icebreaking requirements shall not assume any greater assistance rendered by Canadian icebreakers than was rendered during the past two ice seasons and shall include meeting the demands of United States commerce in all U.S. waters of the Great Lakes and their harbors and connecting channels. (Page 72)

The explanatory statement also states:

Polar Ice Breaking Vessel.—The Committee recognizes the value of heavy polar icebreakers in promoting the national security and economic interests of the United States in the Arctic and Antarctic regions and recommends $555,000,000, which is the requested amount. The total recommended for this program fully supports the Polar Security Cutter program of record and provides the resources that are required to continue this critical acquisition.

Polar Star.—The recommendation includes $15,000,000 to carry out a service life extension program for the POLAR STAR to extend its service life as the Coast Guard continues to modernize its icebreaking fleet. (Page 73)